WHEN I WAS SMALL, my family travelled to Oberammergau, a Bavarian village at the feet of the Alps where the houses are painted with fairytales and the winter snows are deeper than the doorknobs. We lived there on and off over a few years with the cowbells and woodcarvings, the Kofel mountain, the Bavarians with their rules, and the Passion Play for which Oberammergau is best known.

I have fond and vivid memories of this time. The summers of my recollection are sunny green grass and bees and buttercups, the river Ammer where my brother threw his toy helicopter, and paper windmills and glass jewels stuck in the earth between the flowers in the garden of Frau Jaekel who lived in the village. But the winters... that cold winter when my parents had to tear the wallpaper from the walls for a fire to warm the old house we had just moved into. In the very deep snows, we couldn't drive our van to buy groceries and so my mum pulled us and the shopping along on a wooden sledge which still sits upstairs in my parents' house. Nuns used to leave us gifts of food on the door handle, I wore a pinstriped snowsuit, and Schnuffel the St Bernard ate icicles.

(that's a little Rima driving the sledge with my mum and brother)

I have been thinking lately... this snow in all its blue lustre and creaking cold beauty has stayed with me always, in my imagination and in my paintings. Every winter I paint a snowy picture which usually turns into my Christmas cards. There is snow in

this painting of mine, and

this and

this and

this and

this and

this. I don't know where it comes from. I think if the world in my paintings were to be hunted for on a map, it would reside somewhere North, somewhere where there are white nights in the summer and dark days in the winter, somewhere blanketed in snow. Perhaps an Eastern-European Scandinavia? A Finnish Siberia? A Germanic Russia? A Russian Svalbard? A Saami Holland? Wherever it is the snow hangs heavy on the conifer forests and logs are stacked under low hung eaves for fires by which stories will be told.

These thoughts led me back to the books of my childhood, three in particular, which I think played an enormous part in carpeting my imagination with winter.

The first, a well loved favourite, given to me when I was quite young I think, is

The Fox and the Tomten by Astrid Lindgren, after a poem by Karl-Erik Forsslund and illustrated by Harald Wiberg. This is a story based on the Scandinavian folkloric character of the Tomte which I have

written about before.

He is a protector of the homestead so long as you leave him a bowl of porridge on winter nights; in this tale he reliquishes his porridge to Reynard the fox to stop him eating the chickens. Harald Wiberg's paintings (watercolour I think) have stayed strongly with me, the shadows on snow so blue and moonlit, the still quiet of a snow covered night so well described, the hearth-glowing family interior so warm in contrast with Reynard out in the cold through the window, and the filigree of white branches so delicately frosted.

The second, a book I would read with delicious expectation every Christmas Eve of my youth:

The Night Before Christmas by Clement C Moore and illustrated by Douglas Gorsline. This too was given to me young, and I can still recite the well known poem in my head. The excitement and magic, not just of Christmas for a child, but of snow itself, was conjured in a young me by this book.

"The moon on the breast of the new fallen snow

gave a lustre of midday to objects below."

And the wonderful reindeer entourage arrives over rooftops, bringing sugar canes and bells down chimneys worldwide. The night before Christmas was always far more wonderful than the day itself for me because of all the possibility of strange and impossible rooftop visits and the almost unbearable anticipation of stocking-rustlings and chocolate coins at the bottom of the bed.

The third is a book I have

mentioned before.

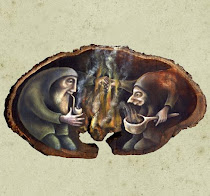

Trubloff by John Burningham is the story of a mouse who wanted to play the balalaika. He lives with his family in the panelling of an inn bar somewhere in Eastern Europe, and is enchanted by the music played by the gypsies who stop at the inn for food and shelter.

Burningham's illustrations are wonderful in their rough scratchy paint-stipply simplicity. I envy his ability to create innocence in deceptively simple brushstrokes. With this book too, a memory of snow was made in me. These skies are grey blizzard skies, and the air feels freezing.

The huge yellow block-printed moon is somehow far away. And have you ever heard of a mouse on skis? Let alone one who can play the balalaika...

Now as well as these favourites, there were many others. I remember well the page in Beatrix Potter's

Tailor of Gloucester when Simpkin the cat ventures out into the snowy town on the one night of the year when all animals can talk.

And those stories like that of the Ant and the Grasshopper when one animal has been diligent in his preparations for winter and the other has frittered summer away and ended up cold and homeless, a little like red-footed Thumbeline, taken in by the mouse, in

this version of the tale illustrated by a genius of watercolour - Lizbeth Zwerger.

There are an awful lot of animals out in the snow in these books aren't there? Mice and foxes and cats and reindeer. I do wonder how their conversations go on that one wonderful night.

And finally I'd like to tell you of another book about an animal out in the snow. Though it is one I have discovered more recently, the beauty of the illustrations must be sung. Gennady Spirin is an artist whose work I have long admired.

This story,

Martha, is a true account of Spirin's young son Ilya finding a wounded crow in the Moscow snow and nursing it back to health. It is a simple tale illustrated exquisitely and should be on everyone's shelf. I love the cover for its black and blood red against white, and the snowflakes all over.

I have a theory that the storybook imagery you experience as a child enters you in a different place to visuals taken in as an adult. There is a separate storehouse for these precious visions, limited in their number as your childhood years, but brighter and more musical by far than the myriad pictures that pass your eyes in later living.

***

In my musings on snowy imagery, I must not forget Pieter Brueghel's beautiful winter paintings. His bare branches against duck-egg sky, his many peasant colours against snowy Dutch landscape, are for me a triumph in painting, and a beauty to aim for.

Here is The Hunters in the Snow:

And here is The Numbering At Bethlehem:

And last I bring you some winter paintings of my own. Over these last weeks I have painted two snowy scenes, both in watercolour, one the tale of a fleeing, what from I do not know, and one of a well loved rooftop visit on the night before Christmas.

Here is Snow Flight Under the Seasky:

(in progress details - click to enlarge)

And here is Father Christmas:

I am taking a little hibernation from blogging for a while, but in the meantime I can highly recommend the

A Polar Bear's Tale blog for a plethora of snowy painting inspiration and other Northern delights.

I wish you all a splendid Wintertime, a happy Christmastime, a magical Yule, wherever you are, may there be hoofprints in the snow and chocolate coins, Christmas Eve rustlings, tales by the fire and love.

***

And I leave you with the childhood Christmas words of an oft-quoted favourite, Dylan Thomas, from A Child's Christmas in Wales:

One Christmas was so much like another, in those years around the sea-town corner now and out of all sound except the distant speaking of the voices I sometimes hear a moment before sleep, that I can never remember whether it snowed for six days and six nights when I was twelve or whether it snowed for twelve days and twelve nights when I was six.

All the Christmases roll down toward the two-tongued sea, like a cold and headlong moon bundling down the sky that was our street; and they stop at the rim of the ice-edged fish-freezing waves, and I plunge my hands in the snow and bring out whatever I can find. In goes my hand into that wool-white bell-tongued ball of holidays resting at the rim of the carol-singing sea, and out come Mrs. Prothero and the firemen.

![]()

THIS WELL KNOWN AND LOVED character has evolved nowadays into the sickly-sweet “acceptable” American Santa Claus, but he has ancient and diverse origins, which are not all so “clean” and indeed may not be so successful in the realm of ringing cash registers!

THIS WELL KNOWN AND LOVED character has evolved nowadays into the sickly-sweet “acceptable” American Santa Claus, but he has ancient and diverse origins, which are not all so “clean” and indeed may not be so successful in the realm of ringing cash registers!![]()