A RED SUN-WHEEL burns bright in the blue sky above a green land that could be this land. The sixteen-spoked wheel represents the Romani Gypsy flag, where a red chakra (wheel) spins over a half blue (for sky), half green (for earth) background. I chose to make this sky-wheel into the fiery sun of inspiration and creation in this Once Upon O'Clock made some months ago for Sarah Bayliss who works with the Romany Theatre Company. In searching for her own Gypsy ancestral roots, Sarah asked me to paint her a clock that represented the traditional Gypsy travelling life.

So I drew a scene amongst the trees with a vardo (traditional travelling wagon) stopped at the laneside and its travelling folk collecting firewood and stoking the fire under a kettle for tea. Their horse grazes and the road winds on toward the horizon. This is the Atching Tan - the Stopping Place, the wonderful camp amongst trees - a place to relax and cook and wash, to find water and let the horses rest and the children play, to make repairs to wagons and to make contact with the locals for work and exchange of goods and services.

The clock was painted on a lovely piece of Yew, and where there was a natural crack in the wood, I extended it with paint to become the road.

And just by the road-crack sits a wagtail, the romano chiriclo (Romany bird). James Hayward in his excellent dictionary of the Romany Language Gypsy Jib, finds no obvious reason for this bird to be named for the Gypsy people, but points out that the connection is strong - the Gypsy Lore Society adopted the wagtail as its emblem with the motto Oke romano chiriklo, dikasa e Kalen - which is Welsh Romany for "Behold a Wagtail and you shall see Gypsies". Indeed all piebald animals are thought to be lucky in Gypsy tradition because they hold both dark and light in them simultaneously.

The colourful painted wagons that we associate with Gypsies were only in fact in widespread use for a matter of decades at the end of the nineteenth century. Before vardos, the Gypsies travelled with horses and carts and put up benders (temporary canvas shelters made from flexible branches of hazel or similar) when they stopped. The use of painted wagons was adopted from the Fairground folk who had begun using them earlier on in that century. The ever more elaborate and brightly painted wagons largely stopped being built with the onset of the First World War, and so this short period of time when the Gypsies lived and travelled in these wonderful decorative vardos has left us with the definitive "romantic" image of Gypsy life.

Because wagons and benders were small, most of life was spent outdoors - a rugged all-weather life, where the fire was the focal point of the Gypsies' days and nights. Indeed the Romany expression for stopping place - Atching Tan - comes from the root verb hatch - to burn, to light a fire. Thus the original meaning of the expression for stopping place was "the place where the fire is lit".

Unlike with my other clocks, I decided to scan this one before I painted the numbers on it, so that you'd be able to buy the painting as a print. Mostly I feel that my clocks don't really work as non-clock prints, but this one seemed a complete scene to me which I hope some of you might enjoy. So here is Atching Tan as a print in my etsy shop now.

|

| Atching Tan - by Rima Staines 2011 - oils on wood - prints available here. |

And when that was done, I painted on the numbers and attached brass clock hands to turn around the fiery wagon-wheel sun in the sky.

The clock now hangs happily on Sarah's wall, where I imagine the woodsmoke from the campfire drifting out of the clock to evoke another time...

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

|

| A Gypsy family and their wagon, Epsom Downs, 1938 © Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent |

... Which I leave behind sadly now to write a little about the life of Gypsies in our time, this time now.

I have felt prompted by the recent violent evictions at Dale Farm, the surrounding coverage in the media and by the often shocking reactions to it amongst the population to express something that I've long noticed about people's attitudes to Gypsies, especially during the time I was travelling myself.

|

| Gallician Gypsies being moved from Wandsworth common, 1911 © Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent |

Any article about the site evictions or another Gypsy-related matter prompts screeds of venomous and ignorant comments, the unbelievable flavour of which can also be seen if you follow the #dalefarm discussions on twitter. For some reason, there remains today an extreme fear of and hatred towards travelling people. This is not just the domain of right-wing governments in Italy and Eastern Europe, this is a widespread attitude of many many people in this country now.

|

| A family of basket sellers at Halstead near Sevenoaks in the early 20th century. © Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent |

And I have been so saddened and shocked by what appears to be an explosion of some common inner repressed shadow, that I wanted to think on this a little.

Almost without fail when you hear people talking about this or that Traveller site, or Gypsy-related report in the media, they will say something like "Oh yes, but they're not real Gypsies, they're just dole-scrounging 'pikies'". Many people seem to have this division in their minds about two distinct kinds of "Gypsies": The romantic wagon-dwelling, music-round-the-campfire-playing, peg-and-lavender-selling, fortune-telling Gypsies Of Yore versus the static-caravan-dwelling, scrap-metal-dealing, child-stealing law-dodgers on the grotty council sites of these days. They believe that the first kind have real "Gypsy blood" and that the others are not the "genuine article" and therefore deserve all the venom directed towards them. This is an interesting and frightening phenomenon which calls to mind other historical questionings of purebloodedness. As Simon Evans says in his brilliant book Stopping Places - A Gypsy History of South London and Kent, this false analysis is a ploy which is frequently used to deny that today's Travellers have a culture and history of their own. Once robbed of their identity, they can be dismissed as 'mere' vagrants, itinerants and scoundrels. In reality of course, Travellers are Travellers, there are no "real" and "fake" versions. It feels like once people have identified the "negative variety" of Travellers, they then give themselves permission to pour all the really venomous hatred, fear, envy and dissatisfaction with their own life onto this group of people.

|

| A bender tent, St Mary Cray, 1870 © Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent |

The common story as to the history of this nomadic people is that they left Rajasthan (based upon the fact that the Romani language is strongly linked to Sanskrit) around a thousand years ago and have been travelling west since. They got called "Gypsies" through a mistaken belief that they'd come from Egypt. The first record of Gypsies in the British Isles comes from 1505 when a witness at a court hearing in Scotland was described as an "Egypcyan woman" who had considerable skill at reading palms. They've been shunned as outsiders wherever they've travelled whilst at the same time taking up and laying down traditions and musics in all the places and cultures they've travelled through.

|

| Inside a bender tent © James Hayward - Gypsy Jib |

With the gradual privatization of common land in the UK, which has become rife during the last part of the 20th century, the Gypsies have found increasingly fewer stopping places on their travels. They used to do a great deal of work as farm labourers, hop picking and suchlike, and farmers would welcome itinerant workers to stay on their land whilst their work was needed, knowing that they'd travel on after the work was done. But the spreading commercialization of farming and the burgeoning of "agribusiness" where traditional farming ways have been swallowed by the soulless money-hungry machine, has meant little more need for travelling farm workers and so the Gypsies had to find other ways of earning their living.

|

| The Hilding family on a hop farm © Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent |

Their journey, in my opinion, has been hampered further in this country by two laws in particular. The first - the 1960 Caravan Sites Act - which sought to regulate the setting up and running of caravan sites, also placed stipulations on farmers who were using itinerant farm workers on their land, requiring the travellers to leave immediately after harvesting had finished. The act also gave councils new powers to evict Travellers from common land which had previously been the land on which they stopped between farm jobs, so they were left without any legal place to park their homes. In 1968 another Caravan Sites Act was passed which attempted to place duties on local authorities to make some provision for travelling people, but it did not specify any time frame in which to do this and so most authorities never fulfilled their obligation before the second of the detrimental acts came along and negated it: The 1994 Criminal Justice and Public Order Act, put in place by the Tory government of the time, repealed the duty of local authorities to provide places for Travellers to stop, as well as pretty much outlawing the travelling way of life altogether:

Section 77 - Power of local authority to direct unauthorised campers to leave land

(1) If it appears to a local authority that persons are for the time being residing in a vehicle or vehicles within that authority's area—

(a) on any land forming part of a highway;

(b) on any other unoccupied land; or

(c) on any occupied land without the consent of the occupier

the authority may give a direction that those persons and any others with them are to leave the land and remove the vehicle or vehicles and any other property they have with them on the land.

(Part of section 77 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994)

This section goes on to state that anyone who fails to comply with this is committing an offence and will be convicted and/or fined accordingly.

|

| Wrotham Heath at the foot of the North Downs in Kent, apple picking time in the late 1940s. This was a popular stopping place which allowed the horses to have an overnight rest before tackling Wrotham Hill. © Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent |

These acts, combined with the unruly spread of towns and suburbs and frantic road building programmes at the latter end of the 20th century meant that the travelling people who had once walked alongside their horses as they pulled their wagons and stopped on common pieces of ground between jobs, were now squeezed and shunned simultaneously by the roaring traffic of modernity and continuously evicted even from the pieces of land they did find to stop on.

|

| Minty Smith with children, 1960s © Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent |

Thus many Gypsies ended up stopping on the council run sites which, every time they were proposed in an area, were objected to left right and centre by local residents who feared mess and violence in their neighbourhoods and couldn't see any reason for them anyway since the Gypsies 'are a nomadic people'. These sites were concrete and soulless places and the council's rules did not allow the Gypsies to continue there any of their life's loves: keeping horses and dogs and sitting around fires under the sky, nor livelihoods such as storing scrap metal for buying and selling (which had become a main source of income for many since seasonal farm work had all but disappeared). These places were effectively ghettos at the grimmest ends of towns: under bypasses or beside municipal dumps. And the sites are fenced round with high walls and barbed wire. You can see in this photograph below of the Murston site near Sittingbourne in Kent, that the 8 foot high concrete fence posts are crooked inwards inferring that the inhabitants are to be kept in - the barbed wire is clearly not there to prevent intruders.

|

| Traveller site in Murston near Sittingbourne, near completion, 1990. Note the crooks at the tops of the concrete fence posts facing inwards. © Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent |

"They cut your friends off, they cut your way of life off and you're basically tied down to one place and really and truly I wonder who did win the war. Was it Hitler? Because we're on a concentration camp now, we got barbed wire around us, we've got fences around us and we're put miles from anywhere, We've got a big river down the bottom of the road there, three lakes if we want to go and do away with ourselves, because this is the ideal place to be depressed - here."

- Albert Scamp (on Murston site)

© Simon Evans

|

| The Murston site with its 8 foot high barbed wire topped fence. The fact that the posts are facing inwards infers that they are to keep the new residents in. © Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent |

|

| A new Traveller site under construction at Ruxley in 1990. It is lined by an 8 foot high concrete wall and is a few feet away from a busy dual carriageway. © Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent |

The glaring gulf between these concrete ghettos and the life on the road the Travellers had known seems to me to be a huge and tragic putting down of a people. There exists a smug and patronizing notion amongst council spokespeople and others that all the Travellers need is to "settle down" and move into houses, which is offensive in the utmost to people whose deep Way Of Life is just not the same as that of settled folk. The travelling is the thing - the life of taking your chattels with you, and stopping beside hedgerows which provide sustenance and stories. Though it may sound romantic, I know from my experience living on wheels that it is damn hard and raw as well. It is all of this - the romance and the rawness, the realness - that Travellers yearn for, and the gradual erosion of the very intrinsic way of their life has been devastating to the soul of them as a people I think.

|

| Traveller girls © James Hayward - Gypsy Jib |

"When I was younger we used to have television and used to watch cartoons, but I would much rather have gone out and listened to my grandad because he used to go on about the really old times - stories that you would never hear about, and we would sit down there for hours and hours just listening to him. We didn't care about all the technology, televisions and toys and playing with them, we just wanted to listen to him all the time, you know, I really miss that. I really miss the old things that he used to go on about and the old remedies. You get all like the aromatherapy stuff that's come out now, all that Travellers used to do back in the olden days, they used to go and find that up hedgerows...

Now that my grandad's dead, I miss him telling me all the stories and all the things he used to go on about because they were so interesting. It was real life, it was about real life."

- Sarah Hilden

© Simon Evans

|

| Sandwich bar, Biggin Hill, 2001 (NB - the irony of both bad and goodwill displayed on this shop door!) © Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent |

And the prejudice and hatred haven't stopped either. So the Travellers are forced into ways of life that are not what once were theirs yet still must endure hatred for being who they are. Some of you may have watched last week's BBC Panorama about the evictions at Dale Farm, where you'll have glimpsed the horrifically nasty flavour of the opinions of the uninformed and fearful opponents of the site. The programme was thankfully quite balanced in its observation of the people and the evictions, but it was almost unbearable to watch. Though the number of supporters who travelled to the site from all over the UK to chain themselves to railings and battle the riot police (who were sent in in place of bailiffs) was heartening, and the genuine warmth and gratitude expressed by the Travellers towards them was wonderful to witness.

The eviction of Court Road, Orpington in 1934.

The police would gather a gang of men from the nearest town or village to manhandle the wagons off, often late at night, still containing sleeping children, or when the families were not present. A man or woman might return home to find the stopping place empty.

© Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent

|

| The eviction of Court Road, Orpington in 1934. © Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent |

The horrors of evictions have not changed over the years, except to become more violent. Here in this collage of eviction footage over the years, Simon Evans has overlayed the testimonies of Travellers powerfully showing the same old tragic story of being forced to move on.

I wonder what the people who dismiss the Dale Farm residents as "just pikies" think has happened to the "real old Gypsies". For it is the granddaughters and grandsons of the folk in these wonderful old photographs who are the residents of the Traveller sites of today. Many people use the argument that Irish Travellers "don't count" somehow, and apparently possess great inside knowledge when they state authoritatively that the "genuine Gypsies" can't stand the Irish Travellers either. All of this is nonsensical, divisive fear-mongering. I think there's a part of these Traveller-haters which deep down is perhaps angry at their own life choices and the comparative freedom of Travelling people who seemingly don't suffer under the same rules and restrictions placed upon "law abiding house-dwellers". They are unable to accept that different people choose to live in different ways, and that those ways might be deeply intrinsic to their culture and way of experiencing the world. I've observed a simultaneous slight envy of the free roaming life coupled with extreme anger at the fact that they can live this life.

|

| A Sussex layby, 1989 © Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent |

And because Travellers are living outside the norm and on the margins of society, they of course stir up all the shadowy fears in people. This place of fear is where the stories of stealing (both property and children) come from.

I have heard many stories that people will happily tell you (especially if you yourself are living in a vehicle) about Travellers and how they stole this or that. But almost always it is a second or third-hand tale. Most people cannot actually tell you a first-hand experience of Gypsy theft. Now, of course I'm not saying that Travellers don't steal things - it would be a blinkered statement that could not be corroborated anyway, but this applies no differently to house-dwellers: there are house dwellers who steal things and commit all manner of terrible crimes, but it doesn't do to assume that the structure you live in has anything to do with whether or not you commit crimes. I'm just interested in the way that stories which bolster the "us-and-them" mindset get passed on and on, and added to a sort of collective storage bank of Reasons To Hate Gypsies, from which anyone can borrow.

|

| Corke's Meadow, St Mary Cray, 1950s. © Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent |

Long-time readers of this blog might remember an incident I recounted of coming face to face with this fear of Travellers when my truck-house was parked in an orchard in Kent. A woman whose house overlooked the orchard one day hurled abusive language and fearful assumptions like "well you might have dogs, you just don't know do you", "I just don't like having to look at you" and fears that many more vehicle-dwellers might turn up the following summer! I was amazed at the reluctance of people to just come and talk, to see what kinds of people were over there, to ask them questions, to give fellow human beings the benefit of the doubt... but the fear was stronger, and the next day a council official with a clipboard heralded the subsequent leave-taking.

|

| Making primrose baskets in Dartford Woods, 1959. © Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent |

Through living a travelling life, I learned that if your house is small and mobile, then when you stop, a lot of your belongings (bikes, buckets, spare firewood, washing, tin baths etc) will have to be put outside, under the vehicle or in the field - which is why a Traveller site can look so wonderfully ramshackle. I got to see from the other side both the warm kindness and the deep-seated fears and misconceptions in people. Since that time, other people have assumed that I lived that life out of necessity rather than choice - that I was forced to live in a vehicle because a house was not available to me. This is fascinating too - this lack of understanding of the plain love of the travelling life, and is related to that patronizing welfare-assumption that you hear/read in news reports about "Gypsy problems" - where they congratulate themselves on working to get the Travellers "into houses".

"Look at Corke's Pit, the way that that disappeared. I was born in Corke's Pit in an old wagon. One of my aunts born me, there wasn't no nurses come there, no doctors. Travellers lived there for years, didn't they? All that was done away with, they built bungalows there, the old prefabs were there. That's where the Travellers made a mistake: from Corke's Pit, they moved into the prefabs, that was the first of Travellers settling down. When they got into them, they didn't like them. We lived in a prefab for about three years and we bought a wagon and moved back out again."

- Joe and Minnie Ripley

© Simon Evans

|

| Traveller children on Cobham site, 1960s © Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent |

What I really wish for is that people would consult their own true, informed and fair judgement every time they come across Travellers, and base their opinions upon that. Not someone else's third-hand story or opinion, but their own judgement rooted in their own fearless and kind interaction with fellow human beings. I wish that people would expect the best of people and speak and act accordingly. I wish they would quietly keep their own counsel, and always approach another person directly and truly to find out their story.

"If I started talking in the Travellers' language, the biggest half of the words [the youngsters] don't know what I'm on about, they don't understand. The main reason is why, is because all the Travellers is not based together, not like it was years ago... but where the Gypsy kids have been parted up, the language is just dying out."

- Bill Smith

© Simon Evans

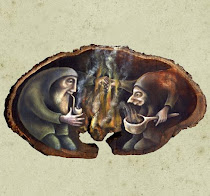

During my time travelling I met a Gypsy woman called Kathleen, who danced her handmade gypsy jig-doll on her knee to the guitar-playing of her husband Charlie around a fire one evening in Devon. Saying goodbye to her the next day, she gave me this card - with a print of a watercolour painting showing an old Gypsy stopping place (unfortunately I don't know the artist's name), and inside, a poem she'd written herself and wanted to pass on to me. I think it paints quite succinctly the life of a Traveller and it's a gift I treasure.

Many of the images and quotations in this post are taken from Simon Evans' excellent book Stopping Places - A Gypsy History of South London and Kent, which I bought in Faversham in Kent whilst I was travelling through, in a small museum of local history. It has proved the most well written, balanced and insightful account of the Travellers' story I've read yet, and it resonates with me particularly because I grew up in the South London / Kent area and so many of these places in the pictures are familiar to me - roads I went down to get to school, and so on. I had friends who would go hop picking as kids with the Gypsies in Kent, and I knew of houses in the area where travellers now lived. If you want a clear and fascinating account of the Gypsy life in the UK, I urge you to buy a copy of this book - it's full of many more wonderful pictures and moving verbatim accounts, not least the wonderful one at the end of this post by Brian Belton, with which Simon Evans also ends his book.

|

| A Reading type Gypsy caravan, 1887 - old well-worn postcard of mine from the Museum of East Anglian Life, Suffolk. |

In truth, I think settled and travelling folk share a great deal these days in terms of the kind of society and world we live in. I feel like the story of the Gypsies in the UK over the last century has been everyone's story: Since industrialisation, we've all had the green freedom taken away from us; we've all been hemmed in, both physically and spiritually by tarmac and city sprawl; we've all had our hats whipped off our heads by the sheer speed of modern life roaring past. The globalization of our minds and daily lives, of our food and our stories, has stopped each individual place mattering. Each individual hedge plant's voice is drowned out by the roar of sameness. Our common places have been sold - owned not by all of us any more. And we've all been herded into concrete ghettos, not free any more to go where we want and live however we want, unwatched, undocumented, wild and real. They've taken away our Atching Tan.

|

| Sarah © Simon Evans - Stopping Places - A Gypsy history of South London and Kent |

"You cannot travel in this society. This society says, 'You cannot live an itinerant way of life.' Now, I think that as a Traveller I can identify other ways of travelling. I can identify other itinerancies. Where are the Travellers going? Well, they're going anywhere and everywhere, but without change you're not going nowhere, you're actually staying exactly where you are. That's the anathema to a Traveller way of life, to stay exactly where you are, you can travel in your mind, you can be a little more transient. I hope that what transient ways of thinking can bring to society, if that's not too grand a word, is the idea that everything moves. If it stays still then it stagnates. You see, Gypsies can't stay where they are. If they stay where they are then they're not a Gypsy. You can start to say, not 'where I've been or where I am', and moan about that, but 'where I want to go', and why I want to go there and the romance and the beauty and the joy of what's around the next corner. That's what really, at the end of the day, created Travellers, it wasn't something in your blood - we'll find a Traveller gene and we'll zap it so we won't have to travel any more. No, it's not that, it's a curiosity, a burning curiosity to know what's over there. I know what's behind me, I have a very good idea of where I actually am, but what I'm really, really interested in is what's over there. That's what I would want to stay dear to, not my caravan, but caravans in the mystical sense of the word, the caravans of the mind."

- Brian Belton

© Simon Evans

|

| © James Hayward - Gypsy Jib |

I leave you with my favourite clip from Tony Gatlif's wonderful film about the Gypsies' thousand year journey - Latcho Drom (meaning good road or journey). I wish that all of us could be like the little boy, and cross over the railway line fearlessly drawn by the warmth and music and wonder of the folk on the other side...