HERE'S A MARVEL & A TALE... This autumn, in the rather marvellous Journal of Fairy Tale Studies published by Wayne State University Press, Marvels & Tales, are three drawings of mine, and a few words too.

Illustrations aren't usually published in the journal, I was told, apart from the occasional turn of the century fairy tale painting. So in a new departure for the journal, they've included my drawings in a Texts & Translations section, for fairy tale responses and interpretations.

Here published below are the three drawings of a favourite fairy tale archetype of mine - The Old Woman In The Woods - and my accompanying article. The drawings were made over a year ago in charcoal and pencil.

But I do urge you to investigate the paper version, which arrived in the post this week. It is published biannually, and is full this autumn with academic musings on giants trampling the earth, stepmothers and narrative disobedience in Pan's Labyrinth, amongst a great deal else...

Also, do tell me if you would buy prints of these drawings, and I'll rustle some up!

{EDIT : Prints for sale in the shop now! Large and small, roll up, roll up! }

{EDIT : Prints for sale in the shop now! Large and small, roll up, roll up! }

________________________________

DRAWING THE OLD WOMAN IN THE WOODS

That old woman. She is sometimes frightening, sometimes kind, always ancient, always cunning, and she always dwells deep in the woods where children become lost.

She who lives in a little house in the forest is a tale-character you'll have met often. Her stories are rich and dark, and hopefully quite terrifying.

This old crone has been a long fascination of mine. My years of loving folktales have repeatedly brought me back to her. I imagine myself as her one day, if not now (though I am young still).

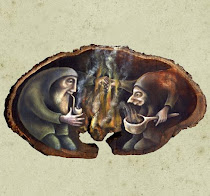

These three drawings are three hag-grandmothers, three ancient crones of fairytale, three faces of the same old woman. Here I have drawn her as Baba Yaga, Red Riding Hood's Grandmother, and Hansel and Gretel's Witch. These are three well recognised guises of the old lady, and my drawings are portraits of each crone with her forest dwelling, because as I see it the place where this old woman lives is a vital key to understanding what she represents.

She appears as an incarnation of the crone or winter aspect of the female deities of old. She is the carrier of wisdom, the guardian of the life and death gates, the overseer of the cold months, and the stewardess of story.

We talk nowadays of long, old, particularly northern, tales as Sagas. But in some quarters it is believed that this word saga was once the feminine of the word sage and that the written sagas of Scandinavia were originally sacred histories kept by female sagas or ‘sayers'. Thus storytelling and wisdom-keeping were entwined in one person: 'She who Speaks' ~ the Oracular Priestess. Her appearance in orally passed down fairy tales seems to stress the importance of story for gaining and nurturing wisdom.

This old lady has many many incarnations in every culture and tradition, but I would like to focus particularly upon the northern snowy countries whose folklores have always drawn me.

The wild forest is a vital aspect of the tale. The tangled thicket is to me a direct representation of wilderness, of the wild nature in us all. It is the feared unknown, the darkness, the habitation of creatures strange and terrifying and of 'otherness'. It is where we must go as lost children to face adversity and death and there find wisdom and rebirth. I wonder whether folktales that feature an old woman in a little hut in the woods are more prevalent in Nordic, Slavonic and Teutonic myth. These are the places where vast particularly conifer and birch forests grow. And on these forest floors grows something else, something powerful and sacred that will show us the way into the gingerbread house...

The Fly Agaric Mushroom (Amanita Muscaria), that little white-spotted red-cap growing deep in the forest that appears so very often in fairy tale illustrations is a mushroom long revered by northern Shamans as a gateway to the Other World. Its hallucinogenic properties could take you to realms of deep knowing, beyond the everyday. I would like to here make the connection between this striking red and white fungus and the 'little hut' in the forest that belongs to that old woman. Both are found deep on the dark woodland floor, both are alike in shape, both take you to the other world. In some tales (such as Hansel and Gretel) children are tempted to directly eat of the house. In others, the journey to find the old lady's dwelling, losing oneself in the forest along the way and facing the terrors within the 'hut' could all be symbolic of the shamanic initiation process one would go through as a result of ingesting the Fly Agaric mushroom. To enter iron-toothed Baba Yaga's skull-lined chicken-legged house, or to approach the devouring wolf inside the hut of Red Riding Hood's grandmother are perhaps to face, whilst in Fly Agaric reverie, the fact of one's own death and other dark truths of nature.

In these tales, children often become lost and unable to return home. This could symbolise the initiatory process of leaving the secure nest and stepping out into the wilderness. And once inside the hut, the tales' protagonists must face adversity of one kind or another. Either they overcome the 'witch' through cunning, or are swallowed and reborn from the belly of the wolf, or they prove themselves bold and true enough to look into the eyes of the skull-lantern.

There are many folkloric 'wood-wife' characters within northern traditions. They are usually wild, hairy or mossy forest-dwelling creatures who are glimpsed on occasion by wanderers into the woods. In Scandinavia, the Huldra is an aged woman, lovely in front but hideous and hollow like a tree behind. Her name comes from a Norwegian root word meaning 'covered' or 'secret', suggesting that she holds keys to hidden gateways. Bavaria's wood-wife, the Dirne-Weible walks about dressed in a red frock carrying a basket of red apples and asking people to accompany her. I wonder whether references to red apples, or indeed red caps and riding hoods in fairy tales, could be a direct hint at the red-hatted mushrooms. Little huts too, it seems to me, have something of the mushroom about them. And therefore tales of journeying to them might hint at the wild wisdom that can be found deep in the forest if you are brave enough to wander away from the path, brave enough to accompany the mossy wood-wife, brave enough to enter the old women's houses where teeth and decay and incinerating ovens are to be found, but also keys to stories and rebirth, in the ancient tradition of the wild.

I hope that in my drawings I have managed to convey the look in the eye of the old ladies of folktale as they pass on to you the story-reins and in so doing invite you into their forest houses of wild knowing.

________________________________

Marvels & Tales is a peer-reviewed journal that is international and multidisciplinary in orientation. The journal publishes scholarly work dealing with the fairy tale in any of its diverse manifestations and contexts. Marvels & Tales provides a central forum for fairy-tale studies by scholars of psychology, gender studies, children's literature, social and cultural history, anthropology, film studies, ethnic studies, art and music history, and others.

This is a pre-copyedited version of an article accepted for publication in Marvels & Tales, volume 24, issue 2, 2010 following peer review. The definitive publisher-authenticated version is available from Wayne State University Press.